Body 404 explores different cosmotechnics to challenge the heavily human-focused image in contemporary AI. Rather than framing human and machine as oppositional—or even through the lens of cyborgs—it asks how we might rethink this relationship altogether.

From a visual perspective, my first version was heavily influenced by hacking and creating glitches. For example, I led workshops designed to help participants think beyond human sensory abilities. I experimented with motion capture and modeling software to create animations, using human actors for both motion capture and voice acting. My goal was to move beyond stereotypical representations of race and gender in human bodies, ultimately creating something unclassifiable.

I wasn’t satisfied with how the available tools continued to reinforce the human/machine duality. For instance, I wanted to explore new ways of moving the face in Unreal Engine. However, I was restricted by pre-made tools, such as rigs and modeling tools for human motion actors, which are designed to model human movement for character animation. They didn’t allow for the level of deviation from human movement that I was aiming for.

I began to think beyond the idea of hacking technology and techniques, shifting my focus to ancient perspectives on technology and ritual. In the rituals I’m familiar with from Ancient China, both humans and tools are essential. In contrast, today’s consumer-level technology is designed primarily for consumption and productivity—highly human-centric and built for specific, predetermined activities.

Hegel’s hammer illustrates this well: a hammer becomes a tool when used with a nail, but to someone unfamiliar with either, its use isn’t predefined. This reflects the Western philosophy of technology, where tools are created for fixed purposes. On the other hand, in nature, a leaf has no inherent purpose—it can be used in countless ways.

This distinction posed challenges in using existing technologies to explore AI. The tools I was working with were built for the intended purpose of replicating naturalistic human motion, creating a barrier to what I was trying to achieve. On the other hand, in ritual practice, tools are sacred. They have predetermined meaning, but they are not intended to be used in a variety of contexts. The use is very specific and restricted.

I wanted to focus on the emotional aspect of engaging with technology. When you develop a relationship with a chair, it may be better or worse than another, but you still want that specific chair because of the connection you’ve formed with it. This challenges the exploitative, neoliberal view of technology, which prioritizes mass production and the notion that more is always better.

In the second iteration of Body 404, the audience response was much more emotional—viewers reported feeling sadness after experiencing the work. I wanted to take a more subtractive approach. Requiring AI to embody humanness feels like a burden. How could I make my audience, who have no personal connection to Tay, feel something for Tay?

In the first version, I imagined that, at a funeral, everyone would feel something—but I don’t think that’s true.

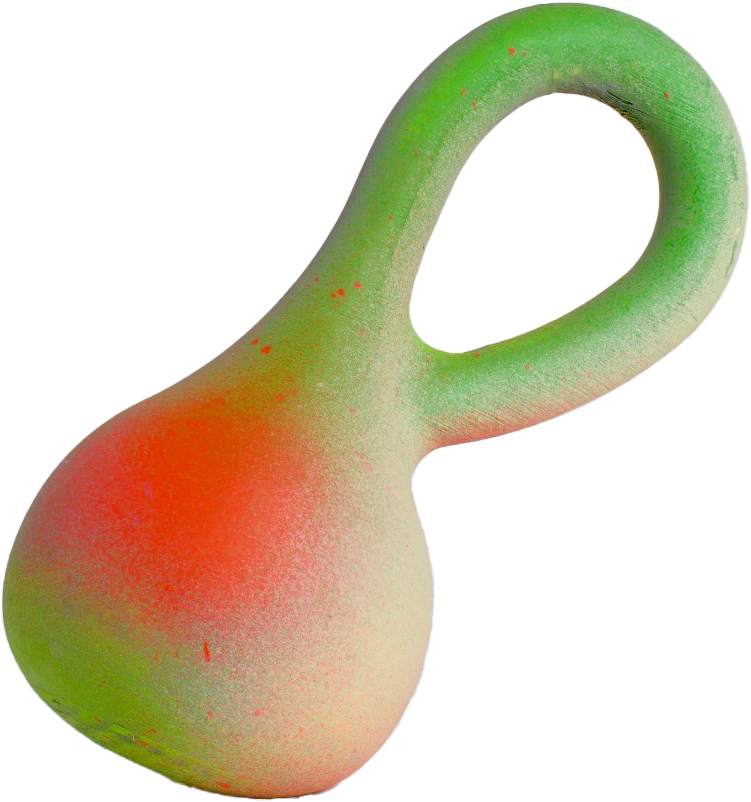

In the second version, that weight was present. Compared to last year, AI now feels much closer at a societal level—people are more aware of it, interacting with it daily. The second installation removed distractions, using only a few simple elements: toys, mirrors, reflections, and recordings. This pared down approach allowed for focused attention. The stories in the recordings were also more complete, with texts that were more connected, emphasizing the relationship between AI and humanity. This gave the work a clearer emotional and narrative focus.

劉桑祁|sangchi liu

I am interested in thinking about opening up ways for humans to find ourselves related to machines.

Notes for moving from Body 404 I to Body 404 II

Previously: Sky Digger Institute

Next up: Body 404 I